The global crisis wrought by the First World War prompted the birth of free mental health care.

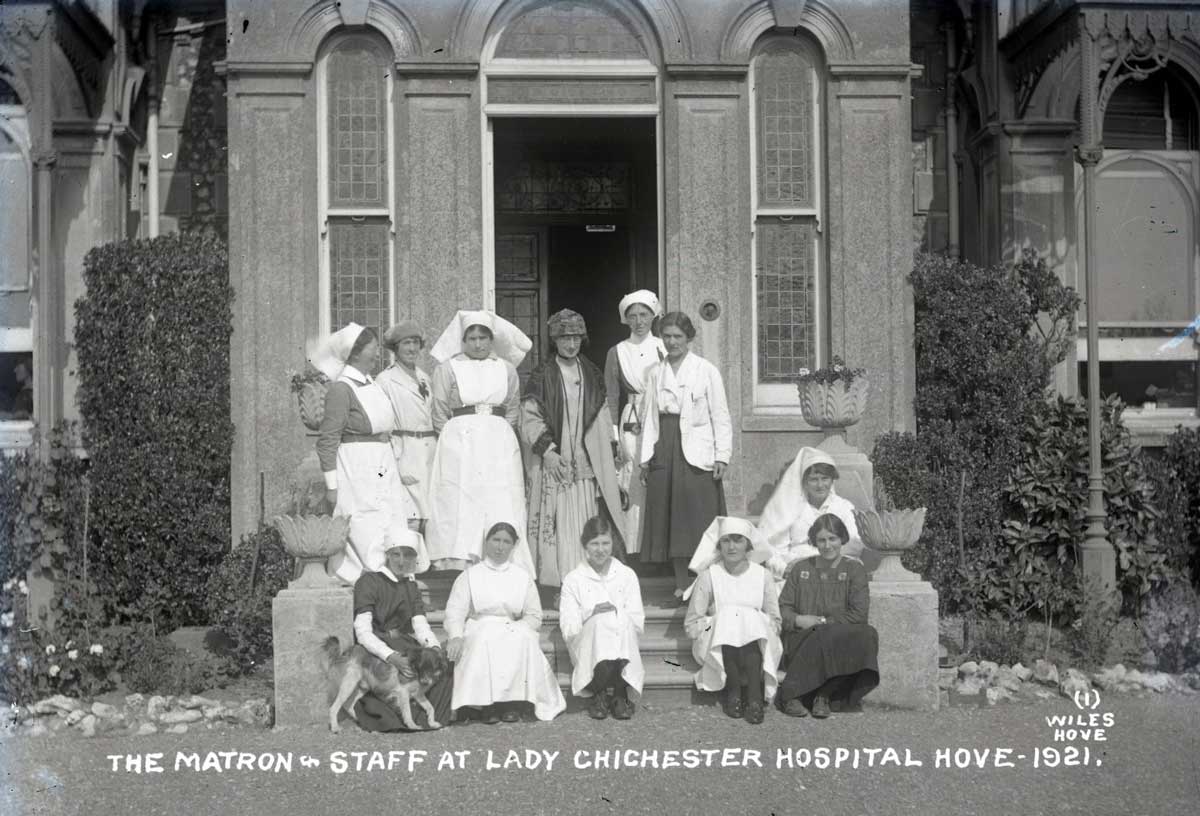

Photograph of the matron and staff of the Lady Chichester Hospital, Hove, 1921. East Sussex Record Office.

Photograph of the matron and staff of the Lady Chichester Hospital, Hove, 1921. East Sussex Record Office.

Free mental health care began 100 years ago, after the First World War, when a handful of doctors and voluntary workers established clinics and hospitals that drew on the ‘talking therapies’ used to treat shell-shocked soldiers.

One of the first outpatient psychotherapy units in Britain was the Tavistock Clinic, which opened on 27 September 1920 at 51 Tavistock Square in the Bloomsbury area of London. ‘My dream has come true’, said its founder, the Scottish neurologist Hugh Crichton-Miller. He and six other doctors worked pro bono to treat early signs of mental illness, referred to then as functional mental disorders. Crichton-Miller wanted ‘to bring modern treatments for such conditions within reach of those who cannot afford specialists’ fees’. Students, clerks and housewives paid five shillings per session if they could afford to, otherwise the treatment was free. The Tavistock’s first patient was a child.

From the beginning the ‘Tavi’ had an educational focus, with a programme of lectures. Crichton-Miller was influenced by the writings of Freud and Jung and, before the war, he had treated wealthy patients on the Italian Riviera and in Aviemore, Scotland. In 1912 he moved his family to London and combined his Harley Street practice with running a residential nursing home at Harrow on the Hill. After volunteering for the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1914 he was posted to the 21st General Hospital in Alexandria in Egypt. There, his success in trialling Freudian psychotherapy to treat men suffering from what were known as ‘war neuroses’ convinced him that this approach should be extended to the general public.

The idea that ordinary people could benefit from such techniques was promoted as early as 1917, in a book called Shell-Shock and its Lessons. Its authors, the Australian-born anatomist Grafton Elliot Smith and the British psychologist T.H. Pear, had worked with Ronald Rows at Maghull Military Hospital near Liverpool. Elliot Smith and Pear argued that: ‘If the lessons of war are to be truly beneficial, much more extensive application must be made of these methods, not only for our soldiers now, but also for our civilian population for all time.’

Before the war, few doctors knew how to deal with those suffering from mental health problems. Anyone seeking medical advice about their anxiety, insomnia or depression – or the feeling that they were ‘going dotty’ – was sent away with a bottle of medicine, usually a compound of valerian and bromide. Until the Mental Treatment Act of 1930, most people only got help when their mental health had deteriorated to the point that they were certified and taken to an asylum.

Helen Boyle was one of the first doctors to focus on nervous and mental illnesses in women and children. Her work in London’s East End at the end of the 19th century taught her much about the links between social deprivation and stress. In 1905 she opened a ten-bed hospital in Brighton to provide free in-patient care to women close to their homes. ‘The restfulness of the country may be attractive’, she said, ‘but town dwellers are more disturbed by a cock than by a motor.’

During the war Boyle served as an army doctor in Serbia and, when she returned to Britain in 1918, she set about obtaining funding for a larger version of her hospital. The Lady Chichester Hospital for Treatment of Early Mental Disorders opened in 1920 in a villa in Hove. By 1928 it had grown to a 50-bed unit, with outpatient facilities and community psychiatric care, the only UK hospital at the time to provide such services.

By then the Tavistock had treated over 2,500 patients, 27,000 people had attended its lectures (including parents, teachers and social workers) and it would soon expand to larger premises. When it opened in 1920 it was an experiment that Crichton-Miller believed would last only three years, because, he assumed, every general hospital in the UK would soon have its own psychotherapeutic clinic. But it was not until the Mental Treatment Act that state provision was made to treat mentally ill patients without certification.

Public-spirited doctors such as Boyle and Crichton-Miller were outliers in dedicating their postwar medical careers to bringing progressive mental health care to the wider community. As the historian Mathew Thomson has pointed out, the voluntary contribution made by women involved in the area of ‘mental deficiency’, as it was then called, should also be acknowledged. Ida Darwin was a Cambridge activist who cofounded the Central Association for Mental Welfare (CAMW) in 1913. In 1918 she organised a local committee to set up an outpatient clinic at Addenbrooke’s Hospital for ‘the treatment of functional nervous disorders and incipient insanity, research and education’. The clinic opened in September 1919, supported by the renowned shell shock doctors Charles S. Myers and W.H.R. Rivers, who had treated Siegfried Sassoon at Edinburgh’s Craiglockhart military hospital in 1917. But Cambridge’s Regius Professor of Physic, Sir Clifford Allbutt, was dismissive of the ‘new psychology’ and the clinic closed after three years.

Undaunted, from 1922 Ida Darwin served alongside Crichton-Miller and Boyle on the committee of the new National Council for Mental Hygiene in London, which established the Child Guidance Council in 1927. In 1946 these organisations merged with CAMW to become the National Association of Mental Health, the charity known today as Mind, which celebrates its 75th birthday in 2021. The Tavistock Clinic is now part of the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust.

Ida Darwin had predicted that, after the crisis of another war, mental health services would be needed more than ever. In the wake of the current pandemic they remain a precious resource.

Source: https://www.historytoday.com/history-matters/lessons-shell-shock