David Prior of the Parliamentary Archives explains why we should be thinking about the Gunpowder Plot unseasonably early, this year.

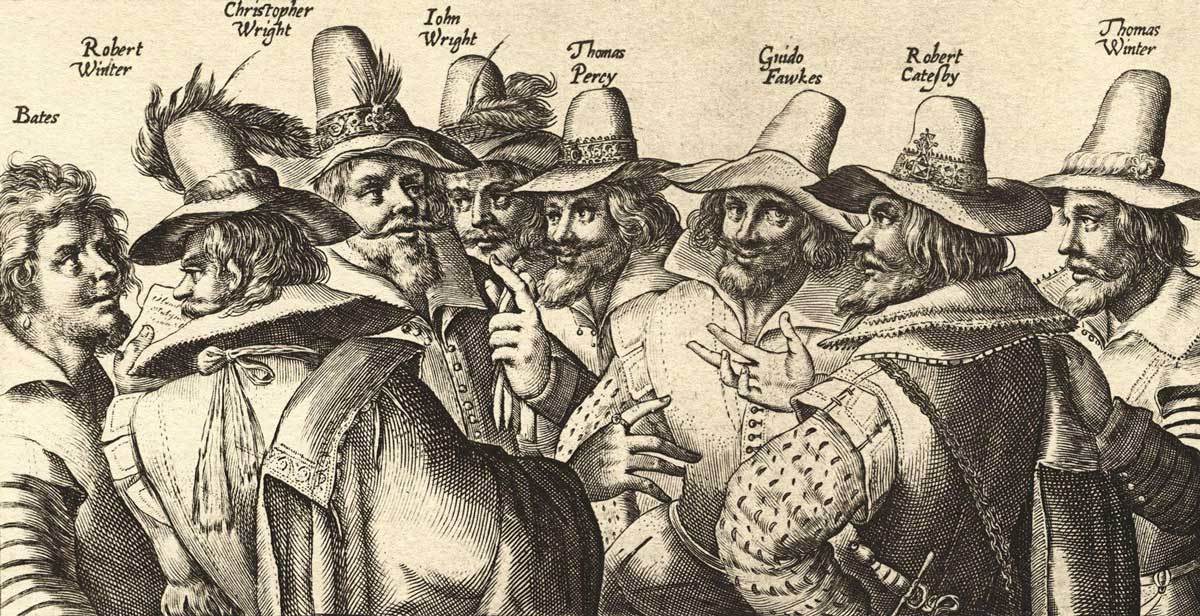

The Gunpowder Plotters, Dutch, c.1605.

The Gunpowder Plotters, Dutch, c.1605.

About three years ago I, with colleagues at the Palace of Westminster, realized that we were approaching the 400th anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot, when Guy Fawkes and a band of fellow conspirators tried to blow up the King as he attended the Houses of Parliament. To many English children, Bonfire Night, with its fireworks and Guy atop a blazing bonfire, used to be – and perhaps still is – one of the most exciting nights of the year, but the reason for it all is not always that obvious. Why did we take part in these strange rituals? What did the Plot mean in 1605, what does it mean now? All this seemed an ideal subject for investigation in an exhibition, staged on the very site of the planned atrocity.

The Plot stands on top of a major faultline that runs through British history since the Reformation, and is inevitably caught up in the events of the modern world in which we live. This becomes apparent on even a cursory glance at the state of England at the accession of James I in 1603. The Protestant Queen Elizabeth herself had been excommunicated by the Pope and her government had taken a hard line against Catholic recusants, seeing them as potential traitors; but with the arrival of the new dynasty Catholic hopes were high that James Stuart would usher in an age of religous toleration. It was not long, however, before disappointment with the King’s policies triggered talk of conspiracies, and moved some to consider that the only route to restoring England to the Catholic fold was to assassinate James and his ministers during the State Opening of Parliament, seize the young Princess Elizabeth and Prince Charles and establish a friendly government that would restore the Catholic faith.

Of the conspirators it is the former soldier Guy Fawkes who became the most notorious, and who has had, for four centuries, the kind of name-recognition a modern-day celebrity would die for (although it literally had to be wrung out of him, as he insisted for several days of interrogation that his name was John Johnson). Fawkes was the man caught in the act but the mastermind behind the conspiracy was in fact the disaffected Warwickshire Catholic gentleman Robert Catesby. The dramatic circumstances in which Fawkes was caught red-handed with almost a ton of gunpowder in an undercroft under the House of Lords, and the subsequent deaths of several key figures in a bloody confrontation in Staffordshire, have assisted Fawkes’ transformation into an icon of the Plot. That this is one of the best-known events in English history also owes much to the fact that an Act of Parliament in 1606 enshrined November 5th as a day of thanksgiving. In addition, the murky story of the affair, with a large cast of characters, and the mysterious appearance of an unsigned letter warning Lord Monteagle not to attend the State Opening of Parliament, is one with which conspiracy theorists can have a field day.

During the seventeenth century, November 5th became established as a popular day for sermons as well as bell-ringing and bonfires. Hostility towards Catholicism – a central part of the appeal of the commemorations in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – gradually became just one thread in a tapestry of general rowdiness and celebration; and it was the figure of Fawkes, rather than the Pope or the Devil, that was placed on top of bonfires. In 1859, in an atmosphere of growing religious toleration, the 1606 Act was abolished. By the 1870s there was increased emphasis on private bonfires and firework parties, and children would collect money in the street to finance them. The rhymes that accompanied these events, though, still left no doubt as to why this was happening: ‘Remember, Remember, the 5th of November/Gunpowder, Treason and Plot’. Bonfire Night private and public events continued through the twentieth century. Now, however, 400 years on, the historic English festival faces competition from the brash American import, Halloween, and the Hindu festival of Diwali, as a late-autumn celebration.

Four centuries on, the Plot remains a difficult subject to tackle, given that religious divides and terrorist violence against the state lie at its heart. Despite this, 2005 will see a range of events examining different aspects of November 1605 in the ‘Gunpowder Trail’, a series of activities staged by a range of institutions in and around London to mark ‘Gunpowder Plot 400’.

Westminster Hall itself will open an exhibition in July, entitled ‘The Gunpowder Plot: Parliament and Treason 1605’. This will explore the subject in a dispassionate way, seeking to engage people with Parliament and Parliamentary history. Exhibits will be drawn from the Parliamentary Archives and the Parliamentary collections of works of art and other institutions. The religious background to the conspiracy will be explained in both a European and an English political context. In mounting the exhibition here – close to the cellar where Fawkes piled his gunpowder, the site of his trial (and that of the other conspirators) on January 27th, 1606, and execution in Old Palace Yard four days later – we will be bringing the story back to its roots.

The Trail also comprises events at: HM Tower of London (telling the Tower’s story of the arrest, imprisonment, torture and death of Fawkes and the plotters); National Portrait Gallery; the National Archives (showing Fawkes’ signed confession); Shakespeare’s Globe (where the public is invited to look again at the Crown Prosecution’s version of events); City of Westminster Archives Centre; Museum of London; Royal Gunpowder Mills (Waltham Abbey); Robert Cecil’s home Hatfield House; Coughton Court (the Warwickshire home of the Throckmorton family); Royal Shakespeare Company; and finally three sites associated with the deeply implicated Percy family: Syon House, Alnwick Castle and Petworth House. For further details about these events visit the Parliamentary website: www.parliament.uk.