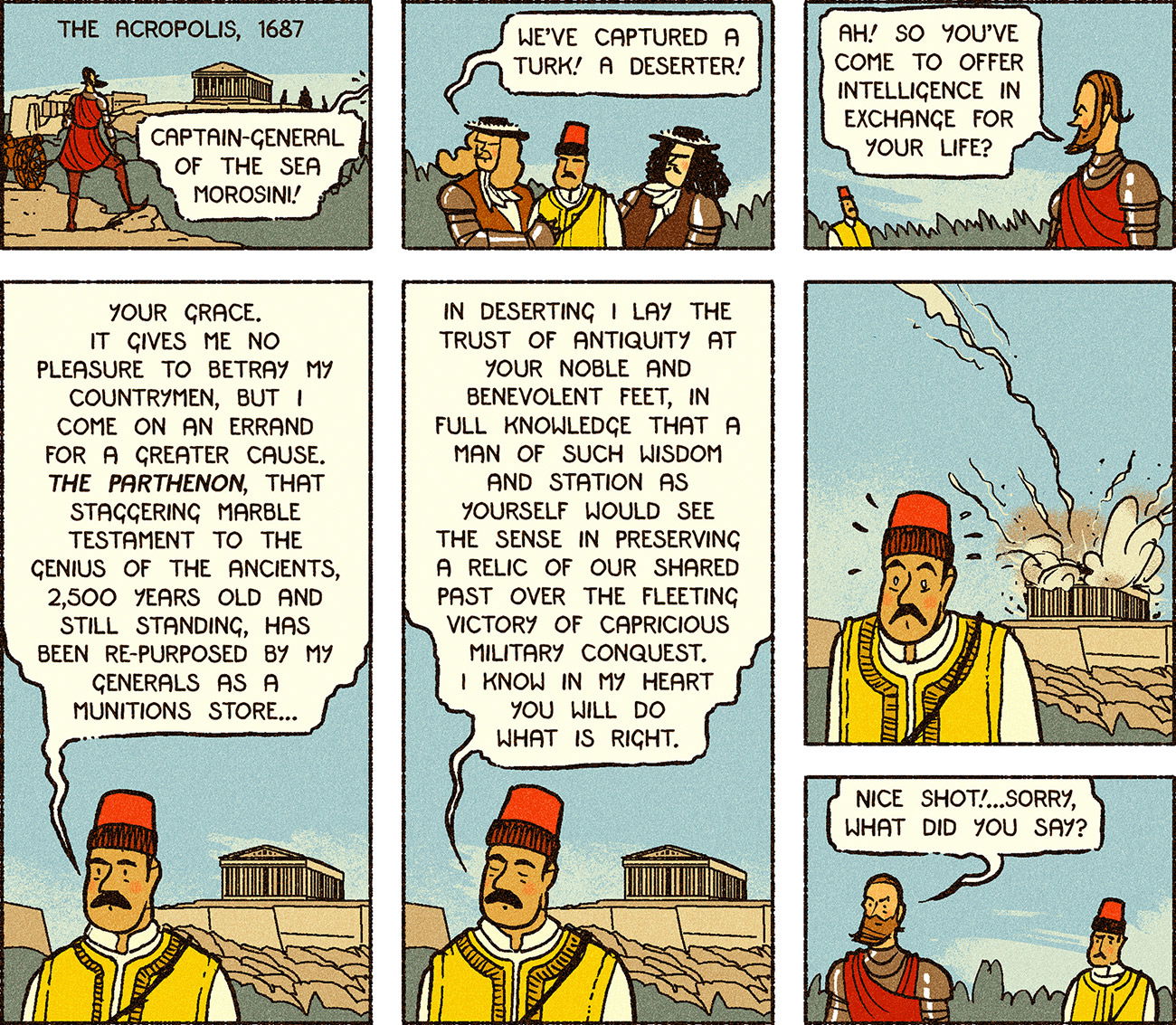

Illustration by R. Fresson.

The Parthenon is Blown Up

The Athenian temple was partly destroyed on 26 September 1687.

The 15-year ‘Great Turkish War’, an effort to oppose the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Europe, was made up of many smaller conflicts, including the Morean War between Venice and the Ottomans, in which the future Venetian doge and fêted Captain-General Francesco Morosini was given orders to seize Athens and its environs from the Turks.

The Acropolis, however, proved a troublesome target. The Turks were dug in on the summit, having heavily fortified the precipitous site, and much of the Turkish population now lived on and around the monuments and in various ancient buildings. Pericles’ Propylaea was still in ruins following the explosion of a powder magazine kept there in 1656, while the Erectheum was a harem. Instead, it was the Parthenon that presented Morosini with the most logical target as he pulled up his artillery on the Philipappus Hill.

Despite the earlier destruction of the Propylaea, the Parthenon was being used by the Turks as a gunpowder store, possibly in the belief that this extraordinary survivor from the Classical Age was protected by the sheer weight of history.

This was not the case. On 26 September 1687 Morosini fired, one round scoring a direct hit on the powder magazine inside the Parthenon. The ensuing explosion caused the cella to collapse, blowing out the central part of the walls and bringing down much of Phidias’ frieze. Many of the columns also toppled, causing the architraves, triglyphs and metopes to come tumbling down.

Morosini later described the shot as ‘fortunate’. Over 300 defenders were killed and fire swept through the Turkish settlement, leading to his recapture of the city. A year later, however, the Venetians were forced to abandon the site as a new Turkish army approached. They considered blowing up the remains of the Parthenon to prevent its further military use, but, thankfully, decided against the plan.